Experimental Use of an Invention

By Richard Stobbe

Inventors must take care that their invention is “new” for it to be patentable. That means the invention hasn’t been disclosed to the public. Trade show announcements, press releases, publications, offering the invention for sale – all of these can be considered a public disclosure, and if disclosure of the invention occurs before the date of filing of the patent application, this disclosure could defeat patentability, since the invention is no longer “new” for patenting purposes.

In Canada and the U.S. there is a 12-month grace period, so the date of prior disclosure is measured against this 12-month period: put another way, patentability may be lost if the invention was disclosed by the inventor more than one year before the filing date of the patent.

So how does this apply to experimental use? How can an inventor test new inventions and avoid the problems associated with public disclosure?

The recent decision in Bombardier Recreational Products Inc. v. Arctic Cat Inc. is interesting in a number of ways, but in this discussion I want to flag one element of the case. Arctic Cat was sued by Bombardier for infringement of certain snowmobile patents, which related to a particular configuration of rider position and frame construction.  Arctic Cat raised a number of defenses and one of them was “prior public disclosure.” Since Bombardier, the patent-holder, tested its prototypes of the snowmobiles on public trails, Arctic Cat argued that, in and of itself, constituted public disclosure, since “someone could have witnessed the rider’s hips above his knees, and the ankles behind the knees, and the hips behind the ankles.”

Unhappily for Arctic Cat, the court dryly dismissed this defense as “another one of those last-ditch efforts.”

Citing an inventor’s freedom to engage in “reasonable experimentation”, the court went on to say: “Since at least 1904, our law has recognized the need to experiment in order to bring the invention to perfection. …In this case, the evidence is that [Bombardier] was conscious of the need for confidentiality and took steps to ensure it would be protected. The experimentation was necessary in view of the many uses that would be available for that new configuration.”

The court noted that, even if a member of the public could have seen the prototype snowmobile “there is little information that is made available to the public while riding the snowmobile on a trail, even for the person skilled in the art. The necessary information to enable is not made available. The invention disclosed in the Patents is not understood, its parameters are not accessible and it would not be possible to reproduce the invention on the simple basis that a snowmobile has been seen on a trail.”

Applying the well-recognized experimental use exception, the court found that experimental use on a public trail did not constitute prior public disclosure of the inventions. Inventors should take care to handle experimental use very carefully.  Make sure you get advice on this from experienced IP advisors.

Related Reading:Â A Distinctly Canadian Patent Fight

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No commentsVCC vs. VCC: Where’s the Confusion?

.

By Richard Stobbe

When we’re talking about trademarks, at which point do we measure whether there is confusion in the mind of the consumer?

We reviewed this issue in 2015 (See: No copyright or trademark protection for metatags). In that earlier decision, Vancouver Community College sued a rival college for trademark infringement, on the basis of the rival college using “VCC†as part of a search-engine optimization and keyword advertising strategy. The court in that case said: “The authorities on passing off provide that it is the ‘first impression’ of the searcher at which the potential for confusion arises which may lead to liability. In my opinion, the ‘first impression’ cannot arise on a Google AdWords search at an earlier time than when the searcher reaches a website.â€Â In other words, it is the point at which a searcher reaches the website when this “first impression†is gauged. Where the website is clearly identified without the use of any of the competitor’s trademarks, then there will be no confusion. That was then.

That decision was appealed and reversed in Vancouver Community College v. Vancouver Career College (Burnaby) Inc., 2017 BCCA 41 (CanLII). The BC Court of Appeal decided that the moment for assessing confusion is not when the searcher lands on the ‘destination’ website, but rather when the searcher first encounters the search results on the search page.  This comes from an analysis of the Trade-marks Act (Section 6) which says confusion occurs where “the use of the first mentioned trade-mark … would cause confusion with the last mentioned trade-mark.”

And it draws upon the mythical consumer or searcher – the “casual consumer somewhat in a hurry“. The BC court reinforced that “the test to be applied is a matter of first impression in the mind of a casual consumer somewhat in a hurry”, and as applied to the internet search context, this occurs when the searcher sees the initial search results.

To borrow a few phrases from other cases, trade-marks have a particular function: they provide a “shortcut to get consumers to where they want to goâ€Â and “Leading consumers astray in this way is one of the evils that trade-mark law seeks to remedy.” (As quoted in the VCC case at paragraph 68).  Putting this another way, the ‘evil’ of leading casual consumers astray occurs when the consumer sees the search results displaying the confusing marks.

On the subject of whether bidding on keywords constitutes an infringement of trademarks or passing-off, the court was clear: “More significantly, the critical factor in the confusion component is the message communicated by the defendant. Merely bidding on words, by itself, is not delivery of a message. What is key is how the defendant has presented itself, and in this the fact of bidding on a keyword is not sufficient to amount to a component of passing off…” (Paragraph 72, emphasis added).

The BC Court issued a permanent injunction against Vancouver Career College, restraining them from use of the mark “VCC†and the term “VCCollege†in connection with its internet presence.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No commentsDrone Patents

By Richard Stobbe

Last month, Amazon made its first delivery via drone with its Prime Air service. Remember, this is an e-commerce company not a drone manufacturer. Amazon is pushing the limits in the use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and is laying the groundwork for an IP protection portfolio for this technology, even where it does not apparently benefit Amazon’s core business. This shows that innovation can open up other product channels that could be licensed, for example, to drone manufacturers. For instance, Amazon’s newest issued patent relates to a mini-drone to assist in police enforcement. Think of a traffic stop which is accompanied by the whine of a small pocket-sized drone that can monitor and record the interaction or chase bad guys.

Other innovations are squarely within Amazon’s core competencies of order fulfillment. Another recently issued patent seeks to protect drones from being hacked and rerouted en route.

Another application filed in April 2016 describes an aerial blimp-like order fulfillment center utilizing UAVs to deliver items from above. This shows that the growth in drone-related patents will not all be related directly to the individual drones, but rather will relate to the evolving ecosystem around the use of UAVs, including remote control technologies, payload innovations, docking infrastructure, and commercial deployments such as the Death Star of e-commerce.

Calgary – 07:00

No commentsIP Licenses & Bankruptcy (Part 2 – Seismic Data)

By Richard Stobbe

What happens to a license for seismic data when the licensee suffers a bankruptcy event?

In Part 1, we looked at a case of bankruptcy of the IP owner.

However, what about the case where the licensee is bankrupt? In the case of seismic, we’re talking about the bankruptcy of the company that is licensed to use the seismic data. Most seismic data agreements are licenses to use a certain dataset subject to certain restrictions. Remember, licences are simply contractual rights.  A trustee or receiver of a bankrupt licensee is not bound by the contracts of the bankrupt company, nor is the trustee or receiver personally liable for the performance of those contracts.

The only limitation is that a trustee cannot disclaim or cancel a contract that has granted a property right. However, a seismic data license agreement does not grant a property right; it does not transfer a property interest in the data. It’s merely a contractual right to use. Bankruptcy trustees have the ability to disclaim these license agreements.

Can a trustee transfer the license to a new owner? If the seismic data license is not otherwise terminated on bankruptcy of the licensee, and depending on the assignment provisions within that license agreement, then it may be possible for the trustee to transfer the license to a new licensee. Transfer fees are often payable under the terms of the license. Assuming transfer is permitted, the transfer is not a transfer of ownership of the underlying dataset, but a transfer of the license agreement which grants a right to use that dataset.

The underlying seismic data is copyright-protected data that is owned by a particular owner. Even if a copy of that dataset is “sold” to a new owner in the course of a bankruptcy sale, it does not result in a transfer of ownership of the copyright in the seismic data, but rather merely a transfer of the license agreement to use that data subject to certain restrictions and conditions.

A purchaser who acquires a seismic data license as part of a bankruptcy sale is merely acquiring a limited right to use, not an unrestricted ownership interest in the data. The purchaser is stepping into the shoes of the bankrupt licensee and can only acquire the scope of rights enjoyed by the original licensee – neither more nor less. Any use of that data by the new licensee outside the scope of those rights would be a breach of the license agreement, and may constitute copyright infringement.

Calgary – 10:00 MT

No commentsGoogle v. The Court: Free Speech and IP Rights (Part 2)

By Richard Stobbe

Last week, hearings concluded in the important case of Google Inc. v. Equustek Solutions Inc., et al.  The Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) will render its judgment in writing, and the current expectation is that it will clarify the limits of extraterritoriality, and the unique issues of protected expression in the context of IP rights and search engines.

In Part 1, I admonished Google, saying “you’re not a natural person and you don’t enjoy Charter rights.” Some commentators have pointed out that this is too broad, and that’s a fair comment.  Indeed, it’s worth clarifying that corporate entities can benefit from certain Charter rights, and can challenge a law on the basis of unconstitutionality. The Court has also held that freedom of expression under s. 2(b) can include commercial expression, and that government action to unreasonably restrict that expression can properly be the subject of a Charter challenge.

The counter-argument about delimiting corporate enjoyment of Charter rights is grounded in a line of cases stretching back to the SCC’s 1989 decision in Irwin Toy where the court was clear that the term “everyone” in s. 7 of the Charter, read in light of the rest of that section, excludes “corporations and other artificial entities incapable of enjoying life, liberty or security of the person, and includes only human beings”.

Thus, in Irwin Toy and Dywidag Systems v. Zutphen Brothers (see also: Mancuso v. Canada (National Health and Welfare), 2015 FCA 227 (CanLII)), the SCC has consistently held that corporations do not have the capacity to enjoy certain Charter-protected interests – particularly life, liberty and security of the person – since these are attributes of human beings and not artificial persons such as corporate entities.

It is also worth noting that the Charter is understood to place restrictions on government, but does not provide a right of a corporation to enforce Charter rights as against another corporation. Put another way, one corporation cannot raise a claim that another corporation has violated its Charter rights. While there can be no doubt that a corporation cannot avail itself of the protection offered by section 7 of the Charter, a corporate entity can avail itself of Charter protections related to unreasonable limits on commercial expression, where such limits have been placed on the corporate entity by the government – for example, by a law or regulation enacted by provincial or federal governments.

There is a good argument that the limited Charter rights that are afforded to corporate entities should not extend to permit a corporation to complain of a Charter violation where its “commercial expression” is restricted at the behest of another corporation in the context of an intellectual property infringement dispute.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

1 commentGoogle v. The Court: Free Speech and IP Rights (Part 1)

By Richard Stobbe

Google Inc. v. Equustek Solutions Inc., et al., the long-running case involving a court’s ability to restrict online search results, and Google’s obligations to restrict search results has finally reached the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC). Hearings are proceeding this week, and the list of intervenors jostling for position at the podium is like a who’s-who of free speech advocates and media lobby groups. Here is a list of many of the intervenors who will have representatives in attendance, some of whom have their 10 minutes of fame to speak at the hearing:

- The Attorney General of Canada,

- Attorney General of Ontario,

- Canadian Civil Liberties Association,

- OpenMedia Engagement Network,

- Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press,

- American Society of News Editors,

- Association of Alternative Newsmedia,

- Center for Investigative Reporting,

- Dow Jones & Company, Inc.,

- First Amendment Coalition,

- First Look Media Works Inc.,

- New England First Amendment Coalition,

- Newspaper Association of America,

- AOL Inc.,

- California Newspaper Publishers Association,

- Associated Press,

- Investigative Reporting Workshop at American University,

- Online News Association and the Society of Professional Journalists (joint as the Media Coalition),

- Human Rights Watch,

- ARTICLE 19,

- Open Net (Korea),

- Software Freedom Law Centre and the Center for Technology and Society (joint),

- Wikimedia Foundation,

- British Columbia Civil Liberties Association,

- Electronic Frontier Foundation,

- International Federation of the Phonographic Industry,

- Music Canada,

- Canadian Publishers’ Council,

- Association of Canadian Publishers,

- International Confederation of Societies of Authors and Composers,

- International Confederation of Music Publishers and the Worldwide Independent Network (joint) and

- International Federation of Film Producers Associations.

The line-up at Starbucks must have been killer.

The case has generated a lot of interest, including this recent article (Should Canadian Courts Have the Power to Censor Search Results?) which speaks to the underlying unease that many have with the precedent that could be set and its wider implications for free speech.

You may recall that this case is originally about IP rights, not free speech rights. Equustek sued Datalink Technologies for infringement of the IP rights of Equustek. The original lawsuit was based on trademark infringement and misappropriation of trade secrets. Equustek successfully obtained injunctions prohibiting this infringement. It was Equustek’s efforts at stopping the ongoing online infringement, however, that first led to the injunction prohibiting Google from serving up search results which directed customers to the infringing websites.

It is common for an intellectual property infringer (as the defendant Datalink was in this case) to be ordered to remove offending material from a website. Even an intermediary such as YouTube or another social media platform, can be compelled to remove infringing material – infringing trademarks, counterfeit products, even defamatory materials. That is not unusual, nor should it automatically touch off a debate about free speech rights and government censorship.

This is because the Charter-protected rights of freedom of speech are much different from the enforcement of IP rights.

The Court of Appeal did turn its attention to free speech issues, noting that “courts should be very cautious in making orders that might place limits on expression in another country. Where there is a realistic possibility that an order with extraterritorial effect may offend another state’s core values, the order should not be made.  In the case before us, there is no realistic assertion that the judge’s order will offend the sensibilities of any other nation. It has not been suggested that the order prohibiting the defendants from advertising wares that violate the intellectual property rights of the plaintiffs offends the core values of any nation. The order made against Google is a very limited ancillary order designed to ensure that the plaintiffs’ core rights are respected.”

Thus, the fear cannot be that this order against Google impinges on free-speech rights; rather, there is a broader fear about the ability of any court to order a search engine to restrict certain search results in a way that might be used to restrict free speech rights in other situations.  In Canada, the Charter guarantees that everyone has the right to: “freedom of …expression, including freedom of the press and other media of communication…” It is important to remember that in Canada a corporation is not entitled to guarantees found in Section 7 of the Charter. (See: Irwin Toy Ltd. v. Quebec (Attorney General), 1989 CanLII 87 (SCC), [1989] 1 S.C.R. 927)

So, while there have been complaints that Charter rights have been given short shrift in the lower court decisions dealing with the injunction against Google, it’s worth remembering that Google cannot avail itself of these protections. Sorry Google, but you’re not a natural person and you don’t enjoy Charter rights. [See Part 2 for more discussion on a corporation’s entitlement to Charter protections.]

Although free speech will be hotly debated at the courthouse, the Google case is, perhaps, not the appropriate case to test the limits of free speech. This is a case about IP rights enforcement, not government censorship.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

1 commentIP Licenses & Bankruptcy Laws (Part 1)

By Richard Stobbe

When a company goes through bankruptcy, it’s a process that can up-end all of the company’s contractual relationships. When that bankrupt company is a licensor of intellectual property, then the license agreement can be one of the contracts that is impacted. A recent decision has clarified the rights of licensees in the context of bankruptcy.

In our earlier post – Changes to Canada’s Bankruptcy Laws – we reviewed changes to the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act (BIA) back in 2009. These changes have now been interpreted by the courts, some seven years later.

In Golden Opportunities Fund Inc. v Phenomenome Discoveries Inc., 2016 SKQB 306 (CanLII),  the court reviewed a license between a parent and its wholly-owned subsidiary. Through a license agreement, a startup licensor, which was the owner of a patent covering an invention pertaining to the testing and analysis of blood samples, licensed a patented invention to its wholly-owned subsidiary, Phenomenome Discoveries Inc. (PDI). PDI, in turn was the owner of any improvements that it developed in the patented invention, subject to a license of those improvements back to the parent company.

PDI went bankrupt. The parent company objected when the court-appointed receiver tried to sell the improvements to a new owner, free and clear of the obligations in the license agreement. In other words, the parent company wanted the right to continue its use of the licensed improvements and objected that the court-appointed receiver tried to sell those improvements without honoring the existing license agreement.

In particular, the parent company based its argument on those 2009 changes to Canada’s bankruptcy laws, arguing that licensees were now permitted keep using the licensed IP, even if the licensor went bankrupt, as long as the licensee continues to perform its obligations under the license agreement. Put another way, the changes in section 65.11 of the BIA should operate to prohibit a receiver from disclaiming or cancelling an agreement pertaining to intellectual property. The court disagreed.

The court clarified that “Section 65.11(7) of the BIA has no bearing on a court-appointed receivership.” Instead the decision in “Body Blue continues to apply to licences within the context of court-appointed receiverships. Licences are simply contractual rights.” (Note, the Body Blue case is discussed here.)

The court went on to note that a receiver is not bound by the contracts of the bankrupt company, nor is the receiver personally liable for the performance of those contracts. The only limitation is that a receiver cannot disclaim or cancel a contract that has granted a property right. However, IP license agreements do not grant a property right, but are merely a contractual right to use. Court-appointed receivers can disclaim these license agreements and can sell or dispose of the licensed IP free and clear of the license obligations, despite the language of Section 65.11(7) of the BIA.

Calgary – 10:00 MT

3 comments

How long does it take to get a patent?

By Richard Stobbe

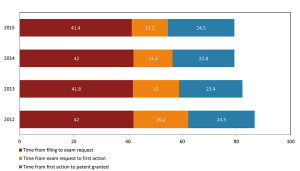

Patent advisors are often asked this question. In Canada, CIPO has published the first-ever IP Canada Report, which contains an interesting trove of IP statistics. Among the infographics and pie-charts is a series of bar graphs showing the time to issuance for Canada patents.

Figure 25 – Average time period in months for the three main stages of the patent process (Courtesy of CIPO)

Over the past four years, the patent office in Canada has been able to shave months off the delivery time, but the average is still in the neighbourhood of 80 months, or roughly 6 1/2 years. Â Certainly some patents will issue sooner, in the 3 – 4 year range, and some will take much longer. Â There are strategies to influence (to some degree) the pace of patent prosecution.

And remember, this is the time to issuance from filing. The time to prepare and draft the application must also be factored in.

Ensure that you get advice from your patent agent and budget for this period of time, it’s a commitment. Â More questions on patenting your inventions? Contact us.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No comments“Place of origin” as a trademark in Canada

By Richard Stobbe

The Canadian trademarks office has released a Practice Notice in order to clarify current practice with respect to applying the descriptiveness analysis to geographical names.

In our earlier post on this topic (Trademark Series: Can a Geographical Name be a Trademark?), we noted that a geographical name can be registrable as a trademark in Canada. The issue is whether the term is “clearly descriptive or deceptively misdescriptive†in the English or French languages of the place of origin of the goods or services.

The Practice Notice tells us that a trademark will be considered a “geographic name” if the examiner’s research shows “that the trademark has no meaning other than as a geographic name.” It’s unclear what this research would consist of. (A search in Google Maps? An atlas?)

Even if the mark does have other meanings, other than as a place name, the mark will be still considered a geographical name if the trademark “has a primary or predominant meaning as a geographic name. The primary or predominant meaning is to be determined from the perspective of the ordinary Canadian consumer of the associated goods or services. If a trademark is determined to be a geographic name, the actual place of origin of the associated goods or services will be ascertained by way of confirmation provided by the applicant.” (Emphasis added)

In some case, the “actual origin” of products may be easy to determine – where, for example, apples are grown in British Columbia, then it stands to reason that “British Columbia” would be clearly descriptive of the place of origin and thus clearly descriptive of the goods. Apples are likely to be grown and harvested in one location. But how would one determine the “actual origin” of, say, a laptop which is designed in California, with parts from Taiwan and China, assembled in Thailand?

If the examiner decides that the geographic name is the same as the actual place of origin of the products, the trademark will be considered “clearly descriptive” and unregistrable. If the geographic name is NOT the same as the actual place of origin of the goods and services, the trademark will be considered “deceptively misdescriptive” since the ordinary consumer would be misled into the belief that the products originated from the location of that geographic name.

It’s worth noting that the place of origin of the products is not the same as the address of the applicant. The applicant’s head office is irrelevant for these purposes.

Need assistance navigating this area? Contact experienced trademark counsel.

Calgary – 07:00 MT

No commentsUse of a Trademark on Software in Canada

.

By Richard Stobbe

Xylem Water Solutions is the owner of the registered Canadian trademark AQUAVIEW in association with software for water treatment plants and pump stations. Â Xylem received a Section 45 notice from a trademark lawyer, probably on behalf of an anonymous competitor of Xylem, or an anonymous party who wanted to claim the mark AQUAVIEW for themselves. This is a common tactic to challenge, and perhaps knock-out, a competitor’s mark.

A Section 45 notice under the Trade-marks Act requires the owner of a registered trademark to prove that the mark has been used in Canada during the three-year period immediately before the notice date. As readers of ipblog.ca will know, the term “use” has a special meaning in trademark law. In this case, Xylem was put to the task of showing “use” of the mark AQUAVIEW in association with software.

How does a software vendor show “use” of a trademark on software in Canada?

The Act tells us that “A trade-mark is deemed to be used in association with goods if, at the time of the transfer of the property in or possession of the goods, in the normal course of trade, it is marked on the goods themselves or on the packages in which they are distributed…” (Section 4)

The general rule is that a trademark should be displayed at the point of sale (See: our earlier post on Scott Paper v. Georgia Pacific). In that case, involving a toilet paper trademark, Georgia-Pacific’s mark had not developed any reputation since it was not visible until after the packaging was opened. As we noted in our earlier post, if a mark is not visible at the point of purchase, it can’t function as a trade-mark, regardless of how many times consumers saw the mark after they opened the packaging to use the product.

The decision in Ashenmil v Xylem Water Solutions AB, 2016 TMOB 155 (CanLII),  tackles this problem as it relates to software sales. In some ways, Xylem faced a similar problem to the one which faced Georgia-Pacific. The evidence showed that the AQUAVIEW mark was displayed on website screenshots, technical specifications, and screenshots from the software.

The decision frames the problem this way: “…even if the Mark did appear onscreen during operation of the software, it would have been seen by the user only after the purchaser had acquired the software. Â … seeing a mark displayed, when the software is operating without proof of the mark having been used at the time of the transfer of possession of the ware, is not use of the mark” as required by the Act.

The decision ultimately accepted this evidence of use and upheld the registration of the AQUAVIEW mark. It’s worth noting the following take-aways from the decision:

- The display of a mark within the actual software would be viewed by customers only after transfer of the software. Â This kind of display might constitute use of the mark in cases where a customer renews its license, but is unlikely to suffice as evidence of use for new customers.

- In this case, the software was “complicated” software for water treatment plants. The owner sold only four licenses in Canada within a three-year period.  In light of this, it was reasonable to infer that purchasers would take their time in making a decision and would have reviewed the technical documentation prior to purchase.  Thus, the display of the mark on technical documentation was accepted as “use” prior to the purchase. This would not be the case for, say, a 99¢ mobile app or off-the-shelf consumer software where technical documentation is unlikely to be reviewed prior to purchase.

- Website screenshots and digital marketing brochures which clearly display the mark can bolster the evidence of use. Again, depending on the software, purchasers can be expected to review such materials prior to purchase.

- Software companies are well advised to ensure that their marks are clearly displayed on materials that the purchaser sees prior to purchase, which will differ depending on the type of software. The display of a mark on software screenshots is not discouraged; but it should not be the only evidence of use. If software is downloadable, then the mark should be clearly displayed to the purchaser at the point of checkout.

- The cases have shown some flexibility to determine each case on its facts, but don’t rely on the mercy of the court: software vendors should ensure that they have strong evidence of actual use of the mark prior to purchase. Clear evidence may even prevent a section 45 challenge in the first place.

To discuss protection for your software and trademarks, Â contact us.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsDear CASL: When can I rely on “implied consent”?

.

By Richard Stobbe

Canada’s Anti-Spam Legislation (CASL) is overly complex and notoriously difficult to interpret – heck, even lawyers start to see double when they read the official title of the law (An Act to promote the efficiency and adaptability of the Canadian economy by regulating certain activities that discourage reliance on electronic means of carrying out commercial activities, and to amend the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission Act, the Competition Act, the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act and the Telecommunications Act).

The concept of implied consent (as opposed to express consent) is built into the law, and the trick is to interpret when, exactly, a company can rely on implied consent to send commercial electronic messages (CEMs). There are a number of different types of implied consent, including a pre-existing business or non-business relationship, and the so-called “conspicuous publication exemption”.

One recent administrative decision (Compliance and Enforcement Decision CRTC 2016-428 re: Blackstone Learning Corp.) focused on “conspicuous publication” under Section 10(9) of the Act. A company may rely on implied consent to send CEMs where there is:

- conspicuous publication of the email address in question,

- the email address is not accompanied by a statement that the person does not wish to receive unsolicited commercial electronic messages at the electronic address; and

- the message is relevant to the person’s business, role, functions, or duties in a business or official capacity.

In this case, Blackstone Learning sent about 380,000 emails to government employees during 9 separate ad campaigns over a 3 month period in 2014. The case against Blackstone by the CRTC did not dwell on the evidence – in fact, Blackstone admitted the essential facts. Rather, this case focused on the defense raised by Blackstone. The company pointed to the “conspicuous publication exemption” and argued that it could rely on implied consent for the CEMs since the email addresses of the government employees were all conspicuously published online.

However, the company provided very little support for this assertion, and it did not provide back-up related to the other two elements of the defense; namely, that the email addresses were not accompanied by a “no spam” statement, and that the CEMs were relevant to the role or business of the recipients. The CRTC’s decision provides some guidance on implied consent and “conspicuous publication”:

- The CRTC observed that “The conspicuous publication exemption and the requirements thereof set out in paragraph 10(9)(b) of the Act set a higher standard than the simple public availability of electronic addresses.” In other words, finding an email address online is not enough.

- First, the exemption only applies if the email recipient publishes the email address or authorizes someone else to publish it. Let’s take the example of a sales rep who might publish his or her email, and also authorize a reseller or distributor to publish the email address. However, the CRTC notes if a third party were to collect and sell a list of such addresses on its own then “this would not create implied consent on its own, because in that instance neither the account holder nor the message recipient would be publishing the address, or be causing it to be published.”

- The decision does not provide a lot of context around the relevance factor, or how that should be interpreted. CRTC guidance provides some obvious examples – an email advertising how to be an administrative assistant is not relevant to a CEO. Â In this case, Blackstone was advertising courses related to technical writing, grammar and stress management. Arguably, these topics might be relevant to a broad range of people within the government.

- Note that the onus of proving consent, including all the elements of the “conspicuous publication exception”, rests with the person relying on it. The CRTC is not going to do you any favours here. Make sure you have accurate and complete records to show why this exemption is available.

- Essentially, the email address must “be published in such a manner that it is reasonable to infer consent to receive the type of message sent, in the circumstances.” Those fact-sepecific circumstances, of course, will ultimately be decided by the CRTC.

- Lastly, the company’s efforts at compliance may factor into the ultimate penalty. Initially, the CRTC assessed an administrative monetary penalty (AMP) of $640,000 against Blackstone. The decision noted that Blackstone’s correspondence with the Department of Industry showed the “potential for self-correction” even if Blackstone’s compliance efforts were “not particularly robust”. These compliance efforts, among other factors, convinced the commission to reduce the AMP to $50,000.

As always, when it comes to CEMs, an ounce of CASL prevention is worth a pound of AMPs. Get advice from professionals about CASL compliance.

See our CASL archive for more background.

Calgary 07:00 MST

No commentsTrader Joe’s vs. Irate Joe’s

By Richard Stobbe

In a long-running battle between Trader Joe’s and _Irate Joe’s (formerly Pirate Joe’s, a purveyor of genuine Trader Joe’s products in Vancouver, B.C.), the US Circuit Court of Appeals recently weighed in. We originally covered this story a few years ago.

In Trader Joe’s Company v. Hallatt, an individual, dba Pirate Joe’s, aka Transilvania Trading [PDF], the court considered the extraterritorial reach of US trademarks laws. The Defendant, Michael Hallatt, didn’t deny that he purchased Trader Joe’s-branded groceries in Washington state, smuggled this contraband across the border, and then resold it in a store called “Pirate Joe’s” (although Hallatt later dropped the “P” to express his frustration with TJ’s). Trader Joe’s sued in U.S. federal court for trademark infringement and unfair competition under both the federal Lanham Act and Washington state law. Since Mr. Hallatt’s allegedly infringing activity took place entirely in Canada, the question was whether U.S. federal trademarks law would extend to provide a remedy in a U.S. Court.

In the wake of this decision, Trader Joe’s federal claims are kept alive, although the court dismissed the state law claims against Hallatt.

The court concluded: “We resolve two questions to decide whether the Lanham Act reaches Hallatt’s allegedly infringing conduct, much of which occurred in Canada: First, is the extraterritorial application of the Lanham Act an issue that implicates federal courts’ subject-matter jurisdiction? Second, did Trader Joe’s allege that Hallatt’s conduct impacted American commerce in a manner sufficient to invoke the Lanham Act’s protections? Because we answer “no†to the first question but “yes†to the second, we reverse the district court’s dismissal of the federal claims and remand for further proceedings.”

In plain English, the appeals court has asked the lower court to reconsider the federal claims and make a final decision. Grab a bag of Trader Joe’s Pita Crisps with Cranberries & Pumpkin Seeds … and stay tuned!

Calgary – 08:00 MST

No comments

Licensees Beware: assignment provisions in a license agreement

By Richard Stobbe

Let’s say a company negotiates a patent license agreement with the patent owner. The agreement includes a clear prohibition against assignment – in other words, for either party to transfer their rights under the agreement, they have to get the consent of the other party. Â So what happens if the underlying patent is transferred by the patent owner?

The clause in a recent case was very clear:

Neither party hereto shall assign, subcontract, sublicense or otherwise transfer this Agreement or any interest hereunder, or assign or delegate any of its rights or obligations hereunder, without the prior written consent of the other party. Any such attempted assignment, subcontract, sublicense or transfer thereof shall be void and have no force or effect. This Agreement shall be binding upon, and shall inure to the benefit of the parties hereto and their respective successors and heirs. [Emphasis added]

That was the clause appearing in a license agreement for a patented waterproof zipper between YKK Corp. and Au Haven LLC, the patent owner.  YKK negotiated an exclusive license to manufacture the patented zippers in exchange for a royalty on sales. Through a series of assignments, ownership of the patent was transferred to a new owner, Trelleborg. YKK, however, did not consent to the assignment of the patent to Trelleborg. The new owner later joined Au Haven and they both sued YKK for breach of the patent license agreement as well as infringement of the licensed patent.

YKK countered, arguing that Trelleborg (the patent owner) did not have standing to sue, since the purported assignment was void, according to the clause quoted above, due to the fact that YKK’s consent was never obtained: “Any such attempted assignment, subcontract, sublicense or transfer thereof shall be void and have no force or effect.” (Emphasis added) In other words, Â YKK argued that since the attempted assignment of the patent was done without consent, it was not an effective assignment, and thus Trelleborg was not the proper owner of the patent, and thus had no right to sue for infringement of that patent.

The court considered this in the recent US decision in Au New Haven LLC v. YKK Corporation (US District Court SDNY, Sept. 28, 2016) (hat tip to Finnegan). Rejecting YKK’s argument, the court found that the clause did not prevent assignments of the underlying patent or render assignments of the patent invalid, since the clause only prohibited assignments of the agreement and of any interest under the agreement, and it did not specifically mention the assignment of the patent itself.

Thus, the transfer of the patent (even though it was done without YKK’s consent) was valid, meaning Trelleborg had the right to sue for infringement of that patent.

Both licensors and licensees should take care to consider the consequences of the assignment provisions of their license, whether assignment is permitted by the licensee or licensor, and whether assignment of the underlying patent should be controlled under the agreement.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsHappy Birthday… in Trademarks

ipbog.ca turns 10 this month. It’s been a decade since our first post in October 2006 and to commemorate this milestone …since no-one else will… let’s have a look at IP rights and birthdays.

You may have heard that the lyrics and music to the song “Happy Birthday” were the subject of a protracted copyright battle. The lawsuit came as a surprise to many people, considering this is the “world’s most popular song” (apparently beating out Zeppelin’s Stairway to Heaven, but that’s another copyright story for another time).  Warner Music Group claimed that they owned the copyright to “Happy Birthday”, and when the song was used for commercial purposes (movies, TV shows, commercials), Warner Music extracted license fees, to the tune of $2 million each year. When this copyright claim was finally challenged, a US court ruled that Warner Music did not hold valid copyright, resulting in a $14 million settlement of the decades-old dispute in 2016.

In the realm of trademarks, a number of Canadian trademark owners lay claim to HAPPY BIRTHDAY including:

- The Section 9 Official Mark below, depicting a skunk or possibly a squirrel with a top hat, to celebrate Toronto’s sesquicentennial. Hey, don’t be too hard on Toronto, it was the ’80s.

- Another Section 9 Official Mark, the more staid “HAPPY BIRTHDAY VANCOUVER 1886-1986” to celebrate that city’s centennial. Because nothing says ‘let’s party’ like the words HAPPY BIRTHDAY VANCOUVER 1886-1986.

- Cartier’s marks HAPPY BIRTHDAY (TMA511885 and TMA779496) in association with handbags, eyeglasses and pens.

- Mattel’s mark HAPPY BIRTHDAY (TMA221857) in association with dolls and doll clothing.

- The mark HAPPY BIRTHDAY VINEYARDS (pending) for wine, not to be confused with BIRTHDAY CAKE VINEYARDS (also pending) also for wine.

- FTD’s marks BIRTHDAY PARTY (TMA229547) and HAPPY BIRTHTEA! (TMA484760) for “live cut floral arrangements”

- And for those who can’t wait until their full birthday there’s the registered mark HALFYBIRTHDAYÂ Â (TMA833899 and TMA819609) for greeting cards and software.

- The registered mark BIRTHDAY BLISS (TMA825157) for “study programs in the field of spiritual and religious development”.

- Let’s not forget BIRTHDAYTOWN (TMA876458) for novelty items such as “key chains, crests and badges, flags, pennants, photos, postcards, photo albums, drinking glasses and tumblers, mugs, posters, pens, pencils, stick pins, window decals and stickers”.

- Of course, no trademark list would be complete without including McDonald’s MCBIRTHDAY mark (TMA389326) for restaurant services.

So, pop open a bottle of branded wine and enjoy some live cut floral arrangements and a McBirthday® burger as you peruse a decade’s worth of Canadian IP law commentary.

Calgary – 10:00 MST

Brexit’s impact on IP Rights

By Richard Stobbe

The  UK’s Chartered Institute of Patent Attorneys (CIPA) has released a helpful 12-page summary entitled The Impact of Brexit on Intellectual Property, which discusses a number of IP topics and the anticipated impact on IP rights and transactions, including:

- EPC, PCT and UK patents

- Community trade marks

- Trade secrets

- Copyright

- IP disputes and IP transactions

It is CIPA’s position that IP rights holders should expect “business as usual” in the next few years, since existing UK national IP rights are unaffected, European patents and applications remain unaffected, and the UK Government has not even taken steps to trigger “Article 50” which would put in motion the formal bureaucratic machinery to leave the EU. This step is not expected until late 2016 or early 2017, which means the final exit may not occur until 2019.

Canadian rightsholders who have UK or EU-based IP rights are encouraged to consult IP counsel regarding their IP rights.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

1 comment

Craft Beer Trademarks (Part 2)

By Richard Stobbe

In Part 1 we noted the growth in the craft beer industry in Canada and the U.S., and how this has spawned some interesting trademark disputes.

The case of  Brooklyn Brewery Corp. v. Black Ops Brewing, Inc. (January 7, 2016) pitted New York-based Brooklyn Brewery Corporation against California-based Black Ops Brewing, Inc. in a fight over the use of the mark BLACK OPS for beer. Brooklyn Brewery established sales, since 2007, of its beer under the registered trademark BROOKLYN BLACK OPS (for $29.99 a bottle!). It objected to the use of the name BLACK OPS by the California brewery, which commenced operations in 2015.

The California brewery argued that a distinction should be made between the name of the brewery versus the names of individual beers within the product line, which had different identifying names such as VALOR, SHRAPNEL and the BLONDE BOMBER.  However, this argument fell apart under evidence that the term “Black Ops†appeared on each label of each of the above-listed beers, and there was clear evidence that the California brewery applied for registration of the mark BLACK OPS BREWING in association with beer in the USPTO.

The court was convinced that use of the marks “Black Ops Brewing,†“Black Ops,†and “blackopsbrewery.com†created “a likelihood that the consuming public will be confused as to who makes what product.” An preliminary injunction was issued barring Black Ops Brewing from selling beer using the name BLACK OPS.

Black Ops Brewing has since rebranded to Tactical Ops Brewing.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

2 comments

Alberta’s Prospectus Exemption For Start-Up Businesses

By Richard Stobbe

If you’re a start-up, raising money can feel like a full time job.

Alberta recently brought in a few rule changes which may be of interest: ASC Rule 45-517 Prospectus Exemption for Start-up Businesses (Start-up Business Exemption – PDF) (effective July 19, 2016) is designed to “facilitate capital-raising for small- and medium-sized enterprises on terms tailored to deliver appropriate safeguards for investors.” Second, Alberta is considering the adoption of Multilateral Instrument 45-108 Crowdfunding (MI 45-108) and opened it for a comment period in July.

Crowdfunding (MI 45-108)

If the crowdfunding rules are adopted for Alberta issuers, it would facilitate the distribution of securities through an online funding portal in Alberta as well as across any of the other jurisdictions which have adopted it. Alberta would join Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebéc, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia who have already adopted MI 45-108.

Start-up Business Exemption (Rule 45-517)

As for the new Start-up Business Exemption, here are the essentials as pitched by the ASC:

- Designed for Alberta start-ups seeking to raise funds from Alberta investors

- Aimed at “very modest financing needs”, see the caps below

- Designed to be a simpler and less costly process

- Can be used by issuers wishing to raise funds through their friends and family, or to crowdfund through an online funding portal provided the portal is a registered dealer, and funds are raised only from Alberta investors

- The issuer can issue common shares, non-convertible preference shares, securities convertible into common shares or non-convertible preference shares, among other securities

- Issuer must prepare an offering document

- There is a cap of $250,000 per distribution and a maximum of two start-up business distributions in a calendar year

- Aggregate lifetime cap $1 million

- Designed for a maximum investment amount of $1,500 per investor.  However, through a registered dealer, the maximum subscription from that investor can be as high as $5,000.

- The offering must close within 90 days.

- There is a mandatory 48 hour period for investors to cancel their investment

- The issuer must provide each investor with a specified risk disclosure form and risk acknowledgment form.

Interested in hearing more?

Get in touch with Field Law’s Intellectual Property and Technology Group.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No commentsCraft Beer Trademarks (Part 1)

By Richard Stobbe

Canadians drink a lot of beer.

The number of licensed breweries in Canada has risen 100%  over  the  past  five  years to over 600. In Alberta and B.C. alone, the number of breweries doubled between 2010 and 2015.

Industry trends are shifting, driven by the growth in micro and craft breweries in Canada, a phenomenon mirrored in the U.S., where over 4,000 licensed breweries are vying for the business of consumers, the highest number of breweries in U.S. history.

And with this comes an outpouring of beer-related trademarks.  Brewery names and beer labels invariably lead to the clash of a few beer bottles on the litigation shelf. Let’s have a look at recent U.S. cases:

- The mark ATLAS for beer was contested in the case of Atlas Brewing Company, LLC v. Atlas Brew Works LLC, 2015 TTAB LEXIS 381 (Trademark Trial & App. Bd. (TTAB) Sept. 22, 2015).

- Atlas Brewing Company opposed the trademark application for ATLAS, arguing that there was a likelihood of confusion between ATLAS and ATLAS BREWING COMPANY. The TTAB agreed that there was a likelihood of confusion, since the two marks are virtually identical (the addition of “Brewing Company” is merely descriptive or generic) and the products are identical.

- However, the TTAB ultimately decided that the applicant had earlier rights, since Atlas Brewing Company did not actually sell any products bearing the ATLAS BREWING COMPANY trademark before the filing date for the trademark application. The only evidence related to the pre-sales period – for example, private conversations, letters, and negotiations with architects, builders, and vendors of equipment. The TTAB characterized these as “more or less internal or organizational activities which would not generally be known by the general public”.

- Secondly, there was evidence of social media accounts which used the ATLAS BREWING COMPANY name, but the TTAB was not convinced that this amounted to actual use of the brand as a trademark. “The act of joining Twitter on April 30, 2012, or Facebook on May 14, 2012, does not by itself establish use analogous to trademark use. “

- Interestingly, the TTAB rejected the argument that the beer industry should be treated in a way similar to the pharmaceutical industry: Atlas Brewing Company argued that “there are special circumstances which apply because regulatory approval is required prior to being able to sell beer; and that the beer industry is similar to the pharmaceutical industry, where trademark rights may attach prior to the actual sales of goods, and government approvals are needed prior to actual sales to the general public.” The TTAB countered this by pointing out that pharma companies engaged in actual sales of the product bearing the trademark during the clinical testing phase, prior to introduction into the marketplace. In this case, however, there were no actual sales.

- Thus, the opposition was refused and the application for ATLAS was allowed to proceed.

The old Atlas Brewing Company has since rebranded as Burnt City Brewing, with a knowing wink at the legal headaches: “We’ve all been burned by something, but now we’re back and better than ever.”

Hat tip to Foley Hoag for their round-up of American cases.

Related Reading: How the Craft Brew Boom Is Changing the Industry’s Trademark GameÂ

Calgary – 07:00 MST

1 commentProtective Order for Source Code

By Richard Stobbe

A developer’s source code is considered the secret recipe of the software world – the digital equivalent of the famed Coca-Cola recipe. In Google Inc. v. Mutual, 2016 BCSC 1169 (CanLII),  a software developer sought a protective order over source code that was sought in the course of U.S. litigation. First, a bit of background.

This was really part of a broader U.S. patent infringement lawsuit (VideoShare LLC v. Google Inc. and YouTube LLC) between a couple of small-time players in the online video business: YouTube, Google, Vimeo, and VideoShare. In its U.S. complaint, VideoShare alleged that Google, YouTube and Vimeo infringed two of its patents regarding the sharing of streaming videos. Google denied infringement.

One of the defences mounted by Google was that the VideoShare invention was not patentable due to “prior art†– an invention that predated the VideoShare patent filing date.  This “prior art” took the form of an earlier video system, known as the POPcast system.  Mr. Mutual, a B.C. resident, was the developer behind POPcast. To verify whether the POPcast software supported Google’s defence, the parties in the U.S. litigation had to come on a fishing trip to B.C. to compel Mr. Mutual to find and disclose his POPcast source code. The technical term for this is “letters rogatory” which are issued to a Canadian court for the purpose of assisting with U.S. litigation.

Mr. Mutual found the source code in his archives, and sought a protective order to protect the “never-public back end Source Code filesâ€, the disclosure of which would “breach my trade secret rights”.

The B.C. court agreed that the source code should be made available for inspection under the terms of the protective order, which included the following controls. If you are seeking a protective order of this kind, this serves as a useful checklist of reasonable safeguards to consider.

Useful Checklist of Safeguards

- The Source Code shall initially only be made available for inspection and not produced except in accordance with the order;

- The Source Code is to be kept in a secure location at a location chosen by the producing party at its sole discretion;

- There are notice provisions regarding the inspection of the Source Code on the secure computer;

- The producing party is to test the computer and its tools before each scheduled inspection;

- The receiving party, or its counsel or expert, may take notes with respect to the Source Code but may not copy it;

- The receiving party may designate a reasonable number of pages to be produced by the producing party;

- Onerous restrictions on the use of any Source Code which is produced;

- The requirement that certain individuals, including experts and representatives of the parties viewing the Source Code, sign a confidentiality agreement in a form annexed to the order.

A Delaware court has since ruled that VideoShare’s two patents are invalid because they claim patent-ineligible subject matter.

Calgary – 10:00 MST

No commentsSoftware vendors: Do your employees own your software?

By Richard Stobbe

When an employee claims to own his employer’s software, the analysis will turn to whether that employee was an “author” for the purposes of the Copyright Act, and what the employee “contributed” to the software. This, in turn, raises the question of what constitutes “authorship” of software?  What kinds of contributions are important to the determination of authorship, when it comes to software?

Remember that each copyright-protected work has an author, and the author is considered to be the first owner of copyright. Therefore, the determination of authorship is central to the question of ownership. This interesting question was recently reviewed in the Federal Court decision in Andrews v. McHale and 1625531 Alberta Ltd., 2016 FC 624. Here, Mr. Andrews, an ex-employee claimed to own the flagship software products of the Gemstone Companies, his former employer.  Mr. Andrews went so far as to register copyright in these works in the Canadian Intellectual Property Office.  He then sued his former employer, claiming copyright infringement, among other things.

The former employer defended, claiming that the ex-employee was never an author because his contributions fell far short of what is required to qualify for the purposes of “authorship” under copyright law. The ex-employee argued that he provided the “context and content†by which the software received the data fundamental to its functionality.

The evidence showed that the ex-employee’s involvement with the software included such things as collecting and inputting data; coordination of staff training; assisting with software implementation; making presentations to potential customers and to end-users; collecting feedback from software users; and making suggestions based on user feedback.

The evidence also showed that a software programmer engaged by the employer, Dr. Xu, was the true author of the software. He took suggestions from Mr. Andrews and considered whether to modify the code. Mr. Andrews did not actually author any code, and the court found that none of his contributions amounted to “authorship” for the purposes of copyright.  The court stopped short of deciding that authorship of software requires the writing of actual code; however, the court found that a number of things did not  qualify as “authorship”, including

- collecting and inputting data;

- making suggestions based on user feedback;

- problem-solving related to the software functionality;

- providing ideas for the integration of reports from one software program with another program;

- providing guidance on industry-specific content.

To put it another way, these contributions, without more, did not represent an exercise of skill and judgment of the type of necessary to qualify as authorship of software.

The court concluded that: “It is clearly the case in Canadian copyright law that the author of a work entitled to copyright protection is he or she who exercised the skill and judgment which resulted in the expression of the work in material form.” [para. 85]

In the end, the court sided with the employer. The ex-employee’s claims were dismissed.

Field Law acted as counsel to the successful defendant 1625531 Alberta Ltd.

Calgary – 07:00 MST

No comments